This essay was originally published on the blog of Theater Magazine in tandem with the “Digital Dramaturgies” edition (volume 42, issue 2), 2012.

Over the course of its long history, theater has generally served to reflect, invoke or extend what we understand a human to be. We rig the mirror held up to nature to tilt towards man, displayed within an ever-changing diorama alongside the various institutions of his time: the gods, God, society, the state, the family. One could say that part of the cultural work theater does is to preserve a collective understanding of what a human is and to assure us that we are as we have always been. Theatre’s continual investment in its own history erases difference, sustaining and affirming comprehension across decades and centuries. It maintains a self-image inflected by the tragic subject of Greek theater and the comic wreck of Beckett – and we learn to always, always see ourselves in “Shakespeare, our Contemporary.”

I have been trying to reconcile this assessment of theater with my sense that the vision of eternal man is no longer defensible, and certainly not useful. I began thinking about a theater without human actors, in which that timeworn mirror becomes a glossy screen onto which human audiences project themselves, mediated by data, algorithms and interfaces. We would no longer see ourselves onstage, in other words; we would see an expression of computer-generated, human- ish p rocesses. Our engagement with those processes could become an opportunity to re-think the categories that define theater: the presence of the body, the organization and operation of time, the use of language as a carrier for thought. But the questions most fundamental to my creation of algorithmic theater are about what kinds of screens we are peering into, and what kinds of selves we are hoping to glimpse there.

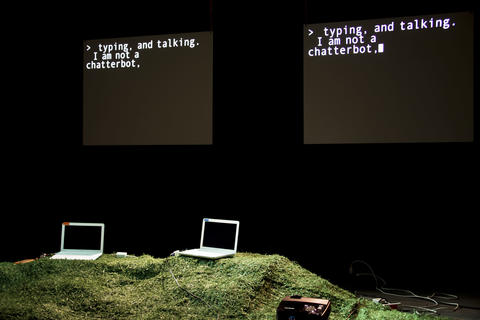

An algorithm is a series of concrete mathematical steps that allow computers “to decide stuff,” in the words of Kevin Slavin.[1] Algorithmic theater shouldn’t be confused with multi-media performance; that is, performance that includes previously recorded material, or makes use of video as décor or alternate space of representation. Instead, algorithmic theater is created by the algorithms themselves, and is not particularly concerned with forms of representation, no matter how newfangled those forms may be. Algorithms start with a data set, and through a progression of specific transformations, they turn inputs into outputs. In this way, given a relatively small number of rules, they can produce a wide variety of results. About three years ago I started collaborating with algorithms as full creative partners, allowing them enormous freedom to operate unsupervised and letting them perform instead of human actors.

In some respects, algorithmic theater conforms to familiar modes of reception: time- based, live, intended for viewing as a linear experience before an audience who views the work in its entirety, from beginning to end. And though algorithms are not, obviously, conscious living beings, they do evoke something like minds at work. They produce thought, they make decisions, they act . Thus, algorithmic theater should be understood as theater, and not as “theatrical installation” or as any other coinage that allows me to pull the end of the slipknot and escape the constraints of my own discipline.

Nevertheless, algorithmic theater challenges the abovementioned “initial axioms” of theater, as a mathematician I met recently put it: embodiment, ephemerality, and most significantly, language as a representation of subjectivity. Though a discussion of each one of these could easily fill up its own essay, I will just sketch out a few basic points about each one.

EMBODIMENT/PRESENCE Embodiment doesn’t necessarily imply mimesis, though that is most commonly how we experience it, but it does demand a body onstage which inhabits the performance, which is or does or shows .

How t he body is deployed within a performance has of course been the subject of three thousand years of exploration, but the necessary presence of a human body onstage, performing actions in front of other human bodies, has rarely been disputed. Aristotle’s origin myth of theater, in which the first actor, Thespis, stepped in front of the chorus one day and announced himself as a character, is book-ended by Peter Brook’s formulation, which reduces theater to nothing more than the performer-spectator relationship: “A man walks across this empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theater to be engaged.”[2]

The customary discourse about presence generally involves rather esoteric appeals to the exchange of energy between performer and audience. At the extreme, you have the Symbolists’ longing for theater as holy communion or Artaud’s call for a theater “in which violent physical images crush and hypnotize the sensibility of the spectator seized by the theater as by a whirlwind of higher forces.”[3] But even in contemporary work, the energetic connection between performer and audience is commonly understood to be theatre’s biggest draw.

Algorithmic theater, however, dispenses with —or at least severely limits the role of— humans onstage. The program is the performer. One might even call it the protagonist, with the audience tracking its choices and changes, instead of those of a human actor. Rather than a mystical exchange of energy between performer and spectator, or a process of identification or “union” between the two, algorithmic performance creates an asymmetric relationship, in which the human spectator confronts something that can’t confront her back. What is produced is not merely the familiar, though still possibly discomfiting, situation of observing oneself observing, or observing oneself being observed – this is not a spectatorship feedback-loop. The loop is broken and the spectator is left radically alone.[4]

This is why I think of these works as anti-esoteric. Audience members may feel an energetic transfer or they may get swept up and absorbed – or they may not. But if t hey do, they have to acknowledge that it’s a feeling of their own making, a trick of their own brains, and there is no objective reality to the impression of communion or contact.

EPHEMERALITY Those who argue that theater is defined by its ephemerality focus on its resistance to reproduction and its appearance and eventual disappearance in time. As Peggy Phelan writes, “Performance’s only life is in the present.”[5] She views this vanishing act as inherently resistant to capitalist modes of reproduction. “Performance clogs the smooth machinery of reproductive representation necessary to the circulation of capital,” she writes (seemingly untroubled by the market forces at work in the creation and dissemination of performances themselves). Underlying the principle of performance as ephemeral is a corollary belief that the secret subject of all theater is the passage of time - and in particular the decay of bodies, which is to say, mortality. Herbert Blau summarizes the idea: “The actor in front of you is dying in front of your eyes. As I am now. That’s literally true, invisibly so. But if you are sufficiently patient, you will see it.”[6]

Algorithmic performance complicates this notion as well. For one thing, algorithms are, one could say, immortal – if all the humans on the planet were wiped out tomorrow, algorithms currently in action would carry on, buying and selling stocks, transmitting messages to and from satellites above the earth, spamming, tracking the popularity of movies on Netflix, and generally doing their business until the power plants failed.[7]

And though an algorithmic performance remains a cooperative situation between the audience and the performance, and any particular evening’s performance takes place in time and is thus literally transient, each and every performance is potentially reproducible down to the last detail. The running through of the algorithm generates a transcript, a stream of data, which can be recalled thousands of times, or never. Each iteration of the program is profoundly contingent, an instance of one possible expression of the formula. The audience’s temporal engagement with that expression may be singular, and will pass; but the performance onstage is immune and indifferent to that disappearance.

Algorithmic theater may shift our understanding of what present tense means in the first place. The process of continuous live choosing amongst variables seems to call forth the future into the current moment; the choices made seem to arrive backwards, as though they were already out there up ahead, waiting to be summoned. Meanwhile the underlying rules of the program, the parameters of its functioning, evoke the past, where the real decisions have already been made, somewhere else, before. This situation stages a paradoxical state of affairs that should be familiar to anyone who follows politics: both closed and open, fundamentally pre-determined and simultaneously full of potential.

REPRESENTATION OF CONSCIOUSNESS THROUGH LANGUAGE The last category is maybe more complex, but it is derived from one of the oldest tenets of Western philosophy: that language is a vehicle for thought, and that theatrical language can therefore “represent consciousness” or the interiority of a human. I’ll use Harold Bloom’s thesis about Hamlet a s illustration. Early in the play, Hamlet says his grief for his father is not just a pose, it’s not just about him wandering around Elsinore looking mopey, or about his black clothes. He has “that within which passes show”: in other words, an inner life that can’t be seen from the outside but that can nevertheless be pointed at by language. Bloom argues that “the internalization of the self is one of Shakespeare’s greatest inventions…”[8] And it’s an invention that has stuck; go to any acting class and you’ll see actors busily trying to decode a playwright’s language to “discover” the internal drives and thought processes of the characters.

One of the interesting situations created by algorithmic performance is that the production of language is disconnected from consciousness. Though I wrote above that the programs produce text and make decisions and do all kinds of things, they have no inherent interiority or desire to communicate from the stage. To put it another way, they have no thoughts that aren’t spoken or acted upon. The language arises from the operation of the software, and at times may suggest consciousness, but never actually issues from it. So understanding language, or more properly seeing through language to the thought “beneath,” is revealed to be an act of imagination on the part of the listener, rather than merely an act of reception.

Computer-generated language seems to oscillate between sound and sense, never quite becoming fully believable human speech, but never settling into a gibberish that would relieve the listener of the burden of trying to understand.[9] The closer the text gets to sense, the more one has the impression of some kind of partial or emerging consciousness; the closer it gets to nonsense, the more one becomes aware of the arbitrary relationship between signifier and signified. With language thus floating free, what claims might it still have to truth? Can an algorithm lie? If it can and does, one may be inclined to ask, like Measure for Measure’s Isabella, “To whom should I complain?” When algorithmically-determined speakers make promises, confess their secrets, or curse their enemies, do their words necessarily hold less weight than when ordinary scripted characters do? Untethering speech from consciousness destabilizes our habitual trust of language as a means of argument, description, revelation, persuasion.

—–

As an algorithm’s operation is a process of successive decisions, perhaps a contrast with another dramaturgy of decision will be illuminating. I am thinking, of course, of Brecht. The “not…but” exercise, for example, as with many of his other techniques, is intended to expose and demonstrate the process of choosing, in order to suggest the availability of alternatives and encourage empowerment in the face of economic, political, social and moral pressures.[10] But we live in a world in which the question of agency is highly disputed, in which our access to choice is circumscribed by the framing of political discourse, by the simultaneous cornucopia and contraction of “options” in our consumer paradise, and, indeed, by algorithms, which filter, consolidate and display certain possibilities while rendering all others invisible.

In Brecht’s work, the monolithic inevitability of capitalism is posited as an illusion that can be undone by critical interventions of choice. In our contemporary culture, however, a culture of constant exhortations to remake ourselves better, younger, happier, sexier, a culture of Oprah’s can-do spirit, we seem to suffer not only from an illusion of powerlessness towards the world at large, but also from one of unlimited power over ourselves. We may feel we can’t do anything about exploitation, environmental calamity or the charades of our political system, but we can remake our own identities in a thousand and one ways. We are drawn by the promise of a liberated autonomy within the marketplace of opinions and personalities; our options appear both infinite and complete. And we seem largely unperturbed by how significantly those options have been pre-selected for us, and how effectively we’ve been persuaded that changing ourselves is a satisfactory substitute for changing the world.

Algorithmic theater is not sci-fi; the pieces I’m making are neither utopian nor dystopian fantasies of a far-off future. We have already given over large areas of decision-making to algorithms, and we have already (mostly) agreed to participate in the conversion of our lives into data, which algorithms will use. Algorithmic theater makes their functioning available for observation and contemplation, so that we may begin to understand not only how they work, but how we work with them.

[1] Slavin’s TED Talk from 2011 is an excellent primer on algorithms and how they work: http://tinyurl.com/3z8ghm5

[2] Peter Brook, The Empty Space, 1968, p.11

[3] Antonin Artaud, The Theatre and Its Double, 1938, pp.82-83

[4] This phrase is a bit misleading; the spectator is not literally alone. She is seated amongst her fellow spectators. It would be interesting to take a look at whether computer performance intensifies the horizontal relationships between audience members. From my own anecdotal experience of a few dozen performances of Hello Hi There , I believe it does.

[5] Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, 1993, p.146

[6] Herbert Blau, Sails of the Herring Fleet: Essays on Beckett, 2000, p.158

[7] In fact, most algorithms already operate largely without human involvement. To take just one example, as of 2010 an estimated 70% of Wall Street trading was conducted by bots, or “high speed traders,” as they’re called, and the figure is almost certainly higher now. Communication between financial algorithms moves far too quickly for human participation. For a good article on autonomous financial algorithms, and the reference for the cited statistic, see http://tinyurl.com/24grzgs

[8] Harold Bloom, The Invention of the Human, 1998, p. 413

[9] For those seeking a good example of algorithmic text, I recommend the delightful Twitter-spam account @Horse_ebooks.

[10] The “not…but” exercise is a rehearsal technique that requires the actor to propose a dialectically opposed action that his character did not choose before asserting what he did choose. “He will say for instance ‘You’ll pay for that’, and not say ‘I forgive you.’ He detests his children; it is not the case that he loves them. He moves downstage left and not upstage right. Whatever he doesn’t do must be contained and conserved in what he does. In this way every sentence and every gesture signifies a decision…” From Brecht on Theatre, 1964, p.137